What was the Columbia Engineering classroom like in the mid-twentieth century?

We share a formative memory from Robert Schaffer ‘46SEAS, ‘52TC, founder and partner emeritus of Schaffer Consulting, from his time as an undergraduate in the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

For more profiles and stories from Engineering alumni, faculty, and staff, click here.

As Robert Schaffer and his classmates filled into the small lecture room in the summer of 1945, they knew they were in for a tough time: Air conditioning did not exist in Pupin Hall—window air units had hit markets in 1932, but would not become widely accessible until the late 1940s—and the day, as he remembers it, was “unbearably hot.”

About one dozen students took their seats amidst the heat. All of them were men, many of whom, like Robert, were attending Columbia on the V-12 Navy College Training Program. On active duty, they sweated stoically in full uniforms.

The professor greeted the class. Theodore Baumeister, known by his students as “Ted,” was younger than his colleagues in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and was only just emerging as a prominent leader and educator in his field. A Columbia Engineering graduate himself, Baumeister had a good-natured curiosity about him that left a positive impression on his students, and they would often get to talking all together at the beginning of the class.

They went back and forth as usual that day, the students and professor alternately giving and taking the floor, when one after the other, students got to voicing their discomforts with the broiling conditions of the room.

Ted addressed these complaints with speculation. Why didn’t they try to turn off the lights?

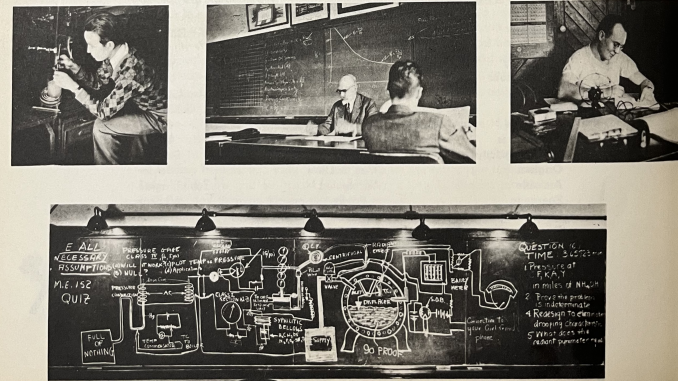

The students scoffed at their professor’s thesis, but Baumeister was up for the challenge. He stood his ground. “Well, let’s see,” he continued. “What are the dimensions of this room?”

Now uncertain of where this was going, but not wanting the playful back-and-forth of the lecturer's preamble to end, the students humored the young professor and engaged his subsequent inquiries.

When, together, they had calculated the approximate volume of air in the room, they used the rating of a light bulb taken from the ceiling to guess its impact on the room’s temperature. They examined the room’s windows, already wide open, and estimated the rate of natural turnover that would simultaneously help to cool the room down.

A few more group calculations later, the professor’s theory solidified: The lights would be responsible for a temperature increase of perhaps three to four degrees fahrenheit.

All satisfied, the lights were switched off, and the rest of the class continued to proceed.

For Robert, who would graduate from the School one year later, this particular classroom memory stands out.

“I had spent many hours in engineering classes by that time, but that was the first time I had seen an engineer actually do engineering—start with a problem and bring to bear the thinking and the calculations that would shed light on a solution.”

Robert would go on to start Schaffer Consulting and develop a unique practice outlined in his book, Rapid Results: How 100-Day Projects Build the Capacity for Large-scale Change. Instead of trudging clients through extensive studies and programs, the practice encourages organizations to focus on smaller goals, which allows them to see rapid results, and then uses their learnings to tackle weightier problems or goals.

Years later, Robert connects the seeds of inspiration from his undergraduate days.

“I sometimes wonder whether the impact of seeing Professor Baumeister's on-the-spot demonstration had some influence on how we did consulting for over 60 years.”

After receiving his bachelor’s degree from Columbia Engineering, Robert matriculated at Teachers College, where he would earn a Doctor of Education in counseling and management psychology. He received the Teachers College Distinguished Alumni Award in 2012.

Robert is now retired, but his firm is still going strong.

Photos from a 1940s yearbook, "The Columbia Engineer."