Can Fusion Energy Play a Role in Mitigating Climate Change?

Collaboration between industry and academia can help accelerate breakthroughs in nuclear fusion in efforts to halt climate change.

Accelerating Commercial Fusion: the Role of Industry and Academia

Tuesday, September 24, 2024 | 3-7 pm

Davis Auditorium, 412 Schapiro CEPSR

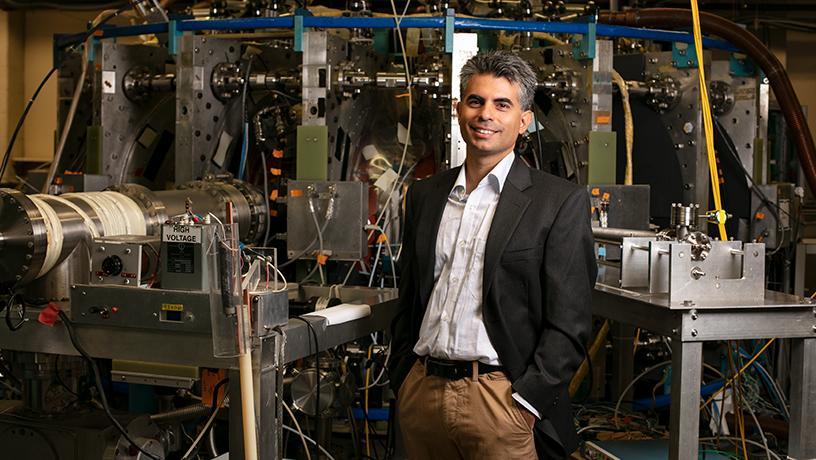

Carlos Paz-Soldan's (pictured) research interests aim to overcome the challenges in harnessing controlled fusion energy.

By far, the energy sector is the biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, representing more than three-quarters of global emissions alone. To achieve net zero over the coming decades, as pledged by more than 140 countries, the global energy system will need a complete transformation. Rapidly weaning off fossil fuels will give the world a fighting chance to limit the worst effects of climate change.

Embracing established renewables like solar, wind, geothermal, and hydropower is key. And recent progress in fusion energy has drummed up excitement for the technology as an abundant, reliable, and emissions-free source of power that could effectively tackle the climate crisis.

“Now more than ever, there is a bigger pull for clean energy technologies due to the ever-greater need of addressing climate change,” said Carlos Paz-Soldan, associate professor of applied physics and applied mathematics at Columbia Engineering. “We hope to deploy fusion technology on a timescale that can help with that problem.”

Paz-Soldan, a faculty member of the Columbia Plasma Physics Lab, conducts both experimental and computational work related to magnetic “bottles” that confine plasma to produce fusion power, and plasma dynamics.

“Fusion has a great many positive attributes, and so it's been called the holy grail of energy sources,” Paz-Soldan said. “It doesn't produce the same level of toxic by-products associated with fission, has a relatively limitless fuel supply, and doesn't rely on the natural elements.”

Nuclear fusion is the reaction that powers active stars, including our own sun. The center of stars is a place so incredibly hot and dense that hydrogen atoms combine to form helium atoms, releasing an immense amount of energy in the process. Recreating this reaction in a controlled laboratory environment on Earth is no small feat — which is why, for most of history, scientists have struggled to produce a fusion reaction that generates more energy than it consumes.

Fusion energy releases no greenhouse gasses, and a power plant could be built anywhere. The main fuel source, hydrogen, is readily found in seawater. In fact, the top inch of water off the Boston Harbor would provide enough hydrogen to power the entire city of Boston for 50 years.

In December 2022, a research team at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s National Ignition Facility (NIF) conducted the first-ever controlled fusion experiment to reach this milestone. A blast from 192 laser beams heated a tiny fuel pellet the size of a pencil eraser to over 300 million degrees Celsius (180 million Fahrenheit). The reaction released a yield of 3.15 megajoules from 2.05 megajoules of incident laser energy, an energy gain factor of 1.5.

Despite the technology’s promise, fusion energy has a long, challenging road ahead before it becomes a practical option. The energy gain factor would need to be much higher, and the logistics and cost of building even a single power plant are significant hurdles. But the prospect of limitless, emissions-free energy is worth the risk — and the expanding private investment in the space suggests that the market agrees.

“There has been a real explosion of private fusion startups in the last several years, and they're really taking the baton to advance the technology towards commercialization,” said Paz-Soldan. “The fusion ecosystem has traditionally been very dominated by the national laboratory complex, where things have been done in the public sector space, and now we have a lot more private sector actors that are able to go faster and take more risks.”

About 45 companies are actively working on commercializing fusion energy, including Commonwealth Fusion Systems, Tokamak Energy, Realta Fusion, and Type One Energy. Paz-Soldan believes that universities like Columbia have an essential role to play in helping industry partners succeed by lending expertise and guiding research and development. Academic researchers can provide the foundational science needed to push fusion out of the laboratory and into the world, where it can meet humanity’s growing demands for clean energy.

“In my opinion, the public has underrated the level of progress that's happened in this field,” said Paz-Soldan. “There are certain technical gaps we know we need to close, but the more investment that we get now, the faster those gaps get closed.”